Spirit of the Stallion – part 2

Tonality

Well you don’t see this everyday when you take beginner band…

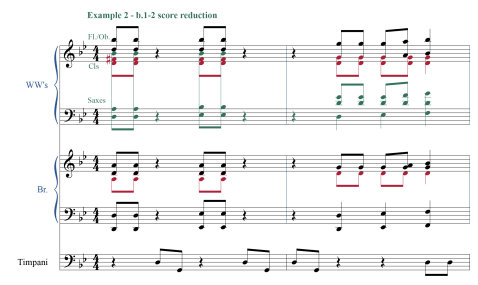

It’s slightly tricky to name what these chords are, so I broke the description up across the staves. Essentially there is an augmented triad over an open 5th bass. Ok, well that’s a little unusual for a beginner band. But wait, there’s more! Notice the minor 9th between the A and Bb! The minor 9th is the last great dissonant interval in western music – not what you typically write for beginners. However, Brian has been very sensible in the way he has orchestrated the chord to ensure that it is successful.

- The brass are playing open octaves and 5ths. Easy to pitch, easy to play in tune and they sound great on brass instruments

- The upper woodwinds are playing the augmented triad, which includes the dissonant Bb (minor 9th above the A). However, the flutes and oboes are in 6ths, the clarinets are in 3rds. The alto sax reinforces the flute Bb in the octave below.

Functionally, this opening chord is a dominant chord – setting up the G minor at bar 4. The half step shift up from D to Eb in the bass implies a phrygian imperfect (or half) cadence in G minor.

Just as there is a sophisticated approach to meter in this piece, there is also a sophisticated approach to key centers

This piece changes key 6 times. The breakdown of the key centers is:

- Bar 1 – G minor

- Bar 4 – G minor

- Bar 12 – C minor

- Bar 20 – C minor

- Bar 28 – F minor

- Bar 36 – F minor

- Bar 42 – G minor

- Bar 48 – Db major

- Bar 56 – G minor

The key changes Gm → Cm → Fm simply move around the cycle of 4ths. Not overly surprising harmonically, but a little unusual for a piece at this level.

Bar 36 is the first statement of the B theme. When this theme is repeated at bar 42, the piece modulates up a step, back to the home key of G minor. Although it is a return to the home key, it doesn’t feel like it. Rather it feels fresh and new.

The most dramatic key change happens at bar 48 here we are suddenly thrust into Db major. We change mode and move a tritone away to the opposite side of the cycle (G→ Db). Then Brian makes a clever use of chromatic harmony to get us back to a D chord, the dominant of G minor, for the return of the A section at bar 56.

The final section, as is typical, stays firmly in the home key of G minor. This grounds the piece harmonically and gives it a sense of finality.

Playability

Despite the number of key centers, all players have very playable parts. Here are some of the reasons why:

- Except for Db major, all the other key centers are the first keys students play in (concert 2 flats, 3 flats, 4 flats). By the end of most beginner method books, students know all these keys.

- By using the natural minor, the harmonic minor’s raised 7th is largely avoided, thereby avoiding more accidentals.

- The melodic material only uses a few notes, largely the first three notes of the scale. As a result at times when it changes key center, some players are not required to play any accidentals.

- At the most dramatic shift to Db major, most players are playing a rhythmic figure on a single pitch. This makes consolidation of new fingerings easier for players.

Making parts playable is the key at this level. Sophisticated compositional devices must be written in a way that is playable. Brian Balmages certainly succeeds in doing that in this piece.

Next time, I’ll take a closer look at how Brian uses orchestration and tessitura to create interest.

Spirit of the Stallion – part 1

I’m currently working on a fantastic piece with my year 8 band (students who are now in their second year of playing) – Spirit of the Stallion by Brian Balmages. It is a grade 1 piece for concert band. You can find a full score here and a recording here.

This piece is both fun to play and has an amazing level of skill and compositional craft in it. Over the next few posts I’ll be looking at some of the aspects of the piece that have caught my eye, starting this week with meter.

Meter

At first glance, there seem to be meter changes everywhere. As a the result, upon handing the piece out, students start curling up in the corner and crying about how inhumane it is. This is understandable, after all there are 27 meter changes in a piece of only 65 bars long. That’s almost a meter change every 2 bars. But if we take a deep breath and look at what is going on, things are not so back.

Firstly, he only uses 2/4, 3/4, and 4/4. The 1/4 note pulse never changes. There are no tempo changes. Phew! Ok, now that your breathing is returning to normal, let’s take a closer look at what is going on…

The form of the piece is:

Intro (3 bars)

A (8)

A (8)

A’ (8)

A (8)

B (6)

B (6)

C (1+4+3)

A (4)

Coda (6)

The introduction is easy – three bars of 4/4. Then the fun begins…

The A sections all follow the same metrical pattern:

4/4 | 3/4 | 4/4 | 3/4 | then four more bars of 3/4

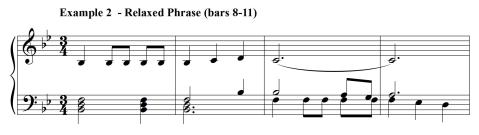

Musically this equates to a 4 bar phrase that is rhythmically tense, followed by a 4 bar phrase the is rhythmically relaxed.

With the accompaniment strongly emphasising beat 1 of each bar and the melody bouncing off of beat 1, this section is much easier to play that it first looks. Notice also that Brian has limited the musical requirements in terms of rhythm and pitch. This enables students to focus on the meter changes.

This is followed by a relaxed phrase that stays in 3/4 and only has simple rhythms.

Repeating this A section pattern four times is very helpful in giving students time to get used to the metrical pattern and to learn its unique groove.

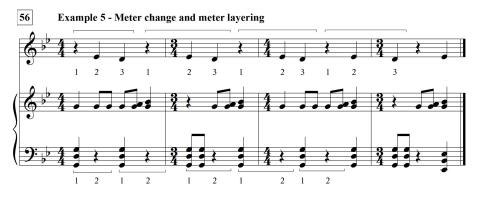

The B section looks easier – the time signature mainly stays in 2/4, but don’t be fooled. In fact, Brian has layered parts in 2/4 over the top of an accompaniment figure that is really in 3/4. Rhythmically this equates to:

Notice that it is not 3/4 playing in the same time as 2/4. The 1/4 note pulse is the same across both parts.

The C section is just in 3/4, no cross meter parts, just straight, simple 3/4.

Just when you couldn’t get enough of changing meters and layering of meters, the final A section cames along. Now we have both going at once. The same shifts between 4/4 and 3/4 as before, but also another part playing across the barline in 3/4 the whole time. To top it off, the accompaniment has also changed slightly to imply 2/4.

Fortunately, this only lasts for four bars before a more straight ahead coda – although straight ahead in this piece means you only change time signature once or twice!

I’m a big believer that if students understand what is going on, they will play it better. So, we’re doing lots of clapping to try and get our heads around everything that happens in this piece meter-wise. Fun and educational…always a great combination.

P.S. You may be wondering what the car is doing at the top of this post. Well, the car is a Mitsubishi Starion. Mitsubishi has a small car called the Mitsubishi Colt (aka a young horse). Legend has it that when Mitsubishi was naming this larger car it was meant to be called the Mitsubishi Stallion (aka an adult horse). But a bit of mis-communication around a Japanese accent speaking English and it wound up being called the Mitsubishi Starion instead. Who knows if it is true, but it’s a great story…

Udala’m – part 2

This post continues looking at the piece Udala’m by Michael Story. You can find my first post here, a full score here and a recording here.

Structurally, Udala’m follows a typical pattern for beginner band works – a slow introduction followed by “the fast bit” (aka the part the students want to play and will endure the slow bit for). I looked at the fantastic polyphonic introduction to this piece in my previous post – now onto the fast bit!

From bar 15, the folk melody is played three times, each time preceded by a two bar introduction. Whilst the introduction is pentatonic, this section just uses the first 5 notes of Bb major. Although it hasn’t changed key as such, the subtle shift in the mode from major pentatonic to major still provides an element of contrast.

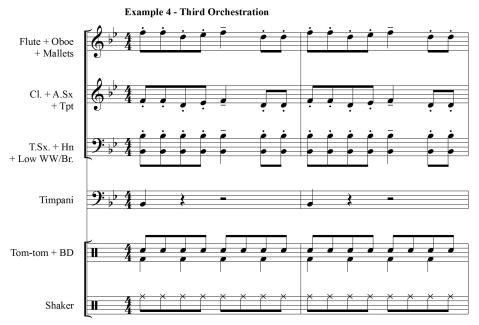

Each statement of the melody is in unison, with a simple rhythmic ostinato accompaniment. Interest is created primarily through orchestration, from small → medium → large.

- 1st time thru (bar 16-25, small orchestration) – the melody is played by the flutes and oboes in unison. The accompaniment is a rhythmic pedal point played by the clarinets

- 2nd time thru (bar 27- 34, medium orchestration) – the melody is played by the clarinets and trumpets in unison. The accompaniment is provided by the low WW/Br. mainly playing a pedal point type ostinato. The alto sax + tenor sax + horns play the same rhythmic pedal point previously played by the clarinets. The percussion loop a one bar rhythmic figure (shaker + tom-tom + bass drum)

Halfway though this section, the flutes and mallet percussion play a simple counter melody.

- 3rd time thru (bar 35 – 44, large orchestration) – the ensemble is divided in half with the upper WW/Br. playing the melody while the lower WW/Br. play the rhythmic ostinato accompaniment.

- Coda (bar 45-48) – the orchestration remains the same while the last phrase is repeated over a dominant pedal.

It is worth noting that the biggest sound is achieved from the ensemble with only two unison lines being played. One of the mistakes people often make when composing and orchestrating for the first time is to try and create a big sound with big chords and many different parts. In fact, the opposite generally works much better. Fewer parts, less complexity equals a bigger sound.

Udala’m – part 1

How many independent parts can a beginner band handle? Two, maybe three at the most (established melody + bass line + counter melody). Surely not five! Yet that is exactly what Michael Story has achieved in his piece Udala’m – an arrangement of a Nigerian folk song. (You can view the full score here and find a recording here.)

How does he do it?

- Pentatonic scale. This piece uses the Bb major pentatonic scale. The nice thing about a pentatonic scale is that there are no sharp dissonances. If fact, if you play all the scale degrees simultaneously as a cluster, you get a dense but consonant sound. This means that any note will basically work against any note, which in turn gives you a great deal of freedom when writing contrapuntal lines.

- Simple melodies. All instruments are playing in an easy range with no awkward or large leaps. Being pentatonic, the melodies are easily understood by the students. (Check out this video to see how easily people can understand a pentatonic scale.)

- Repetition. Each melodic figure is repeated. Once students have mastered their short phrase they can focus on playing that phrase, despite the distraction of the other independent lines.

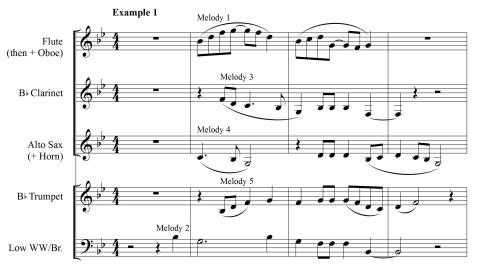

- Staggered entries. He starts with the single melodic line (played by the flutes) and then adds a new melody every two bars (bar 3, 5, 7 and 9). This helps students to be able to understand what is going on and how the pieces “works”.

- Phrase Variation. If all the melodies were the same length and started on beat one of the bar, 5 independent layers would just turn into mush. Michael Story avoids this by varying the phrases length and the starting point as follows:

- Melody 1 – 2 bars, beginning on beat 1

- Melody 2 – 3 bars, beginning with a pickup note on beat 4

- Melody 3 – 2 bars, beginning on beat 2. Therefore, this melody crosses the bar line

- Melody 4 – 3 bars, beginning on beat 1

- Melody 5 – 3 bars, beginning and ending with a quarter rest. This melody doesn’t cross the bar line

- Effective orchestration. Each melodic line is given to a section that can play independently, regardless of the size of the band. There is nothing ground breaking about this orchestration, but is simple and effective.

- Flutes (+Oboes at bar 9)

- Low Woodwinds and Brass

- Clarinets

- Alto Saxes + Horns

- Trumpets

Once again, counterpoint is your friend – especially when writing for young bands. It can be a great way to create interest and complexity from simple elements that are easy to play and understand.

Scorpion!

Scorpion! is a piece by Richard L. Saucedo. It is a loud, energetic, driving piece (tempo is 138bpm) that is all about the vibe it creates rather than beautiful melodies and harmonies. My students enjoyed playing it and stylistically it’s not something I would typically write so I thought it would be useful to look a little more closely at it. You can find the recording and score here.

Form

The piece is 74 bars long and is based on a 4 bar harmonic unit. My outline looks like this:

A(8) | buildup 1 (8+2) |A(8) | A(8) | B(4) | buildup 2 (8+2) | C(9) | A(8) | Tag(8) | unison A(4)

The form doesn’t neatly fit into any predetermined shape, but is probably closest to a kind of rondo form.

Orchestration

One of the first things to notice about this piece is that nearly everyone is playing nearly all the time. This helps to make it loud and also creates a kind of wall of energetic sound effect. It is scored for:

- Flute/Oboe/Bassoon

- Clarinet 1,2/Bass Clarinet

- Alto Sax 1,2/Tenor Sax/Baritone Sax

- Trumpet 1, 2/Horn

- Trombone/Baritone/Tuba

- 3 percussionists

- mallets

- timpani

- Oboe, Horn and Timpani are listed as optional.

With the a few brief exceptions (the most notable being the 4 bar “B” section) the percussion play continuous ostinato figures all the way through.

The brass and saxes are typically playing rhythmic chordal figures. Triads are assigned to Trumpet 1, 2 and Horn and are often a doubled by Alto Sax 1, 2 & Tenor Sax.

The low brass and woodwinds play single note rhythmic ostinatos, most often on a pedal G. They do get the melody for 16 bars on the second “A” section.

The upper woodwinds and mallets (Flute, Oboe, Clarinets, Xylophone, Bells) play a mix of unison/octave ostinatos (typically on a pedal G), or unison/octave melodic lines. In the “C” section, the upper winds are also strengthened by the Alto Saxes.

I’ve found Saucedo’s orchestration approach for a triads and rhythmic ostinato line a useful addition my my bag of tricks.

New vs Hard

Is it new or is it hard?

This is a question I often ask my students. At first glance they look the same to students. However, some things are genuinely difficult to do on an instrument, but other things are just new or I haven’t learnt that yet. As simple example of new, but not hard would be the following examples for a beginner trumpet player:

Both examples are quite easy, requiring the player to only move one finger. However F is one of the first five notes, whereas F# is not. So the second example will seem “hard” to a beginner…until you explain the fingering. At that point what seemed hard turns out to just be “new”.

When writing for junior bands, it is important to realize that some publisher guidelines simply reflect the order in which students learn concepts. This is not the same thing as order of difficulty. Let’s explore this idea with respect to note choice. Typically in a method book the 1st five notes are concert Bb, C, D, Eb, F. This is usually then extended up to include G and down to include A.

So, E natural occurs later in the method books than Eb not because it is harder, but because the method books chooses to start with Bb, C, D, Eb, F (i.e. a major scale). Similarly, A natural comes before Ab, because…well I suspect it’s just because it fits into Bb major, whereas Ab doesn’t. So these two notes could be used in a very beginner piece if you wanted because it will generally take about 30 seconds to explain the new fingering…and you’re done!

This is a good example of a concept a publisher/editor once said to me – namely in any given piece you can ask students to move one step away from what they already know. The emphasis is on ONE step. Only one step and only one per piece!

CAVEAT – I get that not all instruments are the same and although the previous examples are true for all brass and mallet percussion instruments, it’s not necessarily true for every woodwind instrument…but you get the idea.

A counter illustration is probably useful at this point…

Bb is taught straight away, but method books take a long time before they introduce “B” natural because “B” natural is genuinely awkward for trombone (7th position). It will also have big intonation issues for trumpet. It will be very sharp unless the 3rd valve slide is adjusted (which is an intermediate concept). Low brass instruments with only 3 valves will have exactly the same issue. The whole point of a 4th valve on low brass instruments is to solve this intonation issue.

Now, to all the flute players in the room screaming at their screen right now – yes, “B” natural is quite easy on the flute. And while we are at it, yes concert Bb major is an awkward scale for flautists to start with and yes, you would prefer to start flautist off with notes below the break (aka below “D”).

But, I’m glad the flute players were all screaming because it illustrates yet another point…

the deeper your understanding of each instrument of the band is, how it works, what is easy and what is hard for that instrument, the more effectively you can write for band and the better you will be able to exploit the specific capabilities of each instrument to produce great original music.

Say that seven times with a mouthful of marbles!

So in conclusion, moving one step away into something new is OK, genuinely hard is not.

[Photo by Leio McLaren on Unsplash]

Black Is The Color Analysis

One of the ways to get better as a composer is to study the works of other composers. So, I’ve started looking at pieces that I have conducted/rehearsed/performed that I really like. Rather than offer a complete, formal analysis I plan on just highlighting things that I find interesting or can learn from.

The first piece I’ll be looking at is Black Is The Color… by Robert Sheldon. You can find a recording and score here:

Harmony

The piece is in D minor. However rather than an obvious triad to support the opening melody, Sheldon uses a series of 4-note clusters as shown here:

Close harmonies are tricky for young players to hear and are more sensitive to poor intonation than a straight triad, so orchestration choices are critical. Here the cluster is played by clarinets and alto saxes – probably the best choice in this register, at this level. Range wise these clusters could have been played by the upper brass, but intonation is likely to be much worse. Low D for trumpets is sharp (without using the 3rd valve slide), pitching for horns is hard enough without adding a note a tone away. Similarly trombones will have trouble playing notes a tone apart accurately.

Clusters continue to be used throughout the piece by adding a note to a triad. The added note is typically placed in the clarinets or the alto saxes, generally not in the brass.

Rather, the brass play lush triadic voicings:

Notice the use of chord extensions. This is a further example of how Sheldon finds ways to expand the tonal palette beyond simple triads in ways that are playable for students at this level. He also expands out of the basic D minor tonality. In bars 36-39 the progression is Eb → Cm7 → Abmaj7, Abmaj6 → Dbmaj7.

The final chord is a tierce de picardie. The brass are voiced with a straight D major triad, but the woodwinds have an added 2, again placed as a cluster in the clarinets and alto saxes.

Melody

Rather than just play the melody straight through, several phrases are extended by a bar in order to allow the upper winds to play a motivic response (bars 11-12 and bars 16-17). A further phrases extension happens in bars 37-39.

Overall this treatment of the melody creates a sense of space and tranquility, which is highly appropriate given the dedication “In memory of Mark Williams”.

Rhythm

By largely avoiding a simple static chord accompaniment, Sheldon creates a subtle sense of movement and generates interest with a mix of simple rhythmic counterpoint and passing notes.

Percussion

Percussion is used skilfully throughout the piece to add color, interest and to “glue” sections together. All together he uses:

- Bells

- Timpani

- Suspended Cymbal, Snare Drum (snares off), Mark Tree, Triangle

Bells are used to subtly reinforce a single melodic note (b.2, b.43, b.49) or a high woodwind line (b11-12, b16-17). Only once are the used on a strong melodic figure which is also the climax of the piece (b.35-38)

Timpani is used to emphasise key cadence points (b.4-5, b.33-34, b.42-43) and to provide a sustained tonic pedal (b.13-15, b.20-23, b.26-32, b.43-45)

What is interesting is how much the percussion don’t play. But not simply lathering the whole piece with bass drum, snare drum tambourine etc etc it makes the percussion parts much more meaningful. Conversely it makes the percussion even more vital. Every suspended cymbal roll now really matters, it becomes a crucial part of the texture at that point in the music.

I know for me, this is an important lesson to learn. My tendency is to throw lots of percussion at pieces. However if you aren’t careful it becomes the equivalent of the kindergarten painting that has turned brown due to using all of the colors everywhere!

Orchestration

I love they way Sheldon finds ways to use the flutes in their lowest register (b.27-30). How many junior band pieces do you play where the flutes play down to their low D? It works in this piece because they accompany and unison melodic statement by the low brass/woodwinds. The clarinets and alto sax hold 4th in a similar register to the flute line, but the total rhythmic separation (moving line vs sustained note) and tonal separation ensure clarity.

Clarinets also use their lowest register with all clarinets written down to a low E in b.31.

Conclusion

So, not a complete formal analysis of this great piece, but hopefully there’s something in there that you can learn from – I know I have.

Writing again

Earlier this year I posted about how writing wasn’t going so great… well, more like awful actually – at least that’s how it felt a the time. Today I got back into writing again. Even better, I finished something. So how did that happen?

As it turns out I’d already finished something, I just didn’t know it at the time. I’d started with the chord shown below which combines three triads a semitone apart Gb on G on Ab. I liked the crunch this chord has and I could score in such a way as to provide plenty of clarity for players and instrument sections.

I then took some elements from the chord and created some melodic lines like these:

Somewhere in this process I wrote this little waltz theme:

This is when the problems began. I was stuck trying to find a way to meld these ideas together. I really liked the ideas by themselves, but I couldn’t find a way to get convincing from the waltz theme into the compound chord.

My working title was It Cometh… and in order to try and get a handle on the form of the piece and to provide a sense of structure to my writing, I wrote a story line for the piece. People and dancing and a monster slowly approaches. Obviously then the waltz theme is the people dancing, the compound chord would be the final “scream” when the monster arrives. I even wrote a waltz for the monster to dance to (in a vague reference to this classic movie scene). The story was nice, but I still couldn’t get to the final chord ina convincing way. After leaving it for 6 months, today I found the solution. I simply abandoned the chord and the material designed to transition from the waltz theme into the chord. What I was left with was a nice little waltz in rondo form. Happy Days!

The takeaway – sometimes you have to abandon ideas no matter how much you like them because they just don’t fit.

How to cover scales with ketchup (tomato sauce)

This is post isn’t about composing, but I’m so excited about my current approach to doing scales with students that I thought I’d post about it. I’m guessing most of you reading this do some teaching of beginners so hopefully you find it helpful.

If my children are any guide, then the only way to make vegetables palatable is to drown them in tomato ketchup. As I teacher, I’m always searching for the magic ketchup that will make scales palatable to my students. Whilst I’m not sure that such a thing exists, some approaches to scales seem to work better than others.

My students and I have a fundamental difference of opinion. I want my students to be able to play all 12 major/minor scales a a decent tempo, and from memory. My students don’t want to practice scales at all. This cartoon captures their sentiment perfectly…

My current approach to solving this stalemate is based on only doing the first 5 notes of the scale. I start with C major, then I do D minor, then D major, at which point the process repeats itself.The picture illustrates what I mean.

Here’s all the reasons why this approach is cool:

- Five notes fits our short term memory processing abilities much better than the full scale.

- It covers both major and minor scales

- Major and minor scales are integrated with each other. Previously I would do a few major scales, then if there was time and I could be bothered, a few minor scales.

- It avoids explaining a harmonic minor scale with the raised 7th. Notice that this extra complexity occurs exactly where are our short term processing power runs out (at the 7th object/thing).

- Instead minor scales are presented as a variation (or one step away) from a major scale. I know that D minor and C major aren’t the relative major and minor scales in a classical theory sense. But from a learning point of view it is much easier to teach D minor as “take a C major scale, drop the bottom note and add one note on top”. (I use my fingers to demonstrate.)

- It highlights the fact that it is the 3rd note that is the key factor in defining a scale as major or minor. This holds true across modes (Lydian, Major, Mixolydian are all “major” modes with a major 3rd, the remaining modes all sound “minor” with a minor 3rd).

- It makes getting to a new scale a matter of altering one note. It the above example the next scale is E major, but students only have to alter the G to a G#…easy!

- For beginning students it allows them to learn a much wider range of scales within a limited note range. Limited note range isn’t so much of an issue on strings, but on brass instruments it certainly is.

- To get the full octave scale, all that needs to be done is to combine two 5 notes groups. 5 note C major + 5 note G major = full octave C major. Better than that 5 note C major + 5 note G minor = full octave C mixolydian. Similarly, 5 note C minor + 5 note G minor = full octave C dorian. Or, 5 note C minor + 5 note G major = full octave C melodic minor ascending.

Before I finish, I should acknowledge that I got this concept initially from a colleague Steve C — yes he and I do actually sit around talking about how to teach kids scales and have fun doing it (even without ketchup). Thanks Steve!

My Favourite Chord

This is one of my favourite chords:

Personally, I think about it as an Ab(add2)/C rather than the Cm7(b6), but whatever floats your boat. The important thing is what it sounds like.

I love the mix of warmth (generated by the 6th between the lower voices and the 10th between the outer voices), bite (generated by the 2nd between the inner voices and the 7th between alto and bass) and ambiguity/openness (generated by the 4th between the upper voices and the 5th between the soprano and tenor).

A closely related chord that is also a favourite is this one:

I hear this as a minor chord with the added b6, rather than as a major 7 chord. This is similar to the previous chord, but the semitone on the inside rather than a tone gives is a little more bite. It’s interesting that the same 3 notes (C, Ab, Eb) can be heard in 2 different ways depending on the added tone (Bb or G).

Why do you care what my favourite chord is? Well you don’t, except that they might become yours. More importantly for me though is that this is another interesting place to start writing from. The question of “how can I write “X” for young bands and get away with it” has been a fruitful one for me in the past. Here’s hoping that one of these chords will do the same job in the future.

Now it’s time to listen to Appalacian Spring by Aaron Copland. I love what Copland does with major chords!