What I Was Trying To Say Was…

In my last post I talked about “having something to say” when writing for beginner bands (or any band for that matter). In this post I’m going to illustrate what I mean by outlining “what I was trying to say” in a couple of my pieces. (Being Valentine’s Day, I did try to say it with flowers. If they didn’t arrive, please contact your local florist.)

The Forge of Vulcan (pub: Brolga Music)

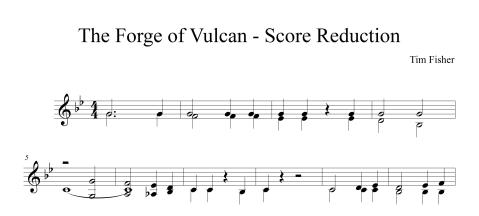

In this piece, I was trying to introduce dissonance in ways that beginner students could cope with and would be able to play successfully. At the time, I had been working through the classic text on counterpoint by Fux – Gradus Ad Parnassum. I realised that if you follow the “rules” about introducing dissonance (prepare it correctly, resolve it correctly), students would/should be able to cope. Hence, I can have the band playing a major 2nd apart for a whole bar (…and loving it!). Notice that the band starts in unison, then moves to the major 2nd, and then resolves to a major 3rd. The dissonance is both prepared and resolved correctly.

Notice that the band starts in unison, then moves to the major 2nd, and then resolves to a major 3rd. The dissonance is both prepared and resolved correctly.

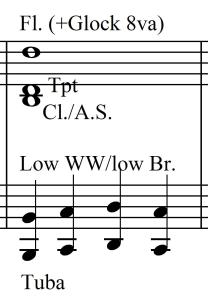

To further improve the clarity of these lines, and to make it easier for students to play, it is scored in a “brass vs woodwinds” kind of way. Initially, the woodwinds all stay static on the “G”, while the brass play the descending line in unison. At bar 5, the roles switch, with the brass remaining static on a “C” whilst the woodwinds play a contrary motion line that starts an octave apart and ends in unison with the brass.

This concept of generating dissonance through oblique motion (i.e. one part moves while the other remains static) extends throughout the piece – e.g. the initial melodic statement in b.9, the B section (b.25-40) and a dominant pedal point later in the piece (b.41-45).

So, I felt comfortable that I had written something with some harmonic interest and gave the low brass as much to do as the other instruments, but what about percussion? The Forge of Vulcan is scored for the following percussion: Glock, Timpani, Snare Drum, Bass Drum, Crash Cymbal, Tambourine, Triangle and Anvil. That should be enough for even the largest percussion section! You could, however, get away with just one player doing Snare Drum and Tambourine with just a little bit of cut ‘n paste.

Tonally, this piece is in C Dorian. It therefore uses the pitch set (Bb major) that the students know at this point, but organises it slightly differently. Personally, I have found it very difficult to write in a straight major key at this level in a way that doesn’t feel like it has already been done.

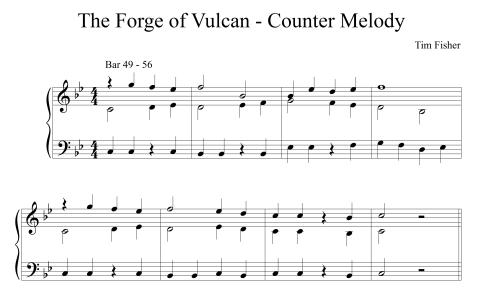

Texturally, the use of a contrapuntal, rather than homophonic (chordal) approach, also helps to make it sound fresher – at least to my ears! For the majority of the piece, there are only 2 lines. But over the final melodic statement, a 3rd line (a countermelody) is introduced into the upper winds and glock parts. At this point in the piece, the rest of the band are playing familiar material and can cope with the addition of another melodic line.

Notice that at times students are playing some quite dissonant harmonies e.g. a minor 7th (F-Eb), a 3 note cluster (G+D+F and C+D+F). It works becuase the lines students play are well constructed and simple within themselves and there is clarity in the way it is orchestrated.

Notice that at times students are playing some quite dissonant harmonies e.g. a minor 7th (F-Eb), a 3 note cluster (G+D+F and C+D+F). It works becuase the lines students play are well constructed and simple within themselves and there is clarity in the way it is orchestrated.

Medieval Fayre (pub: Brolga Music)

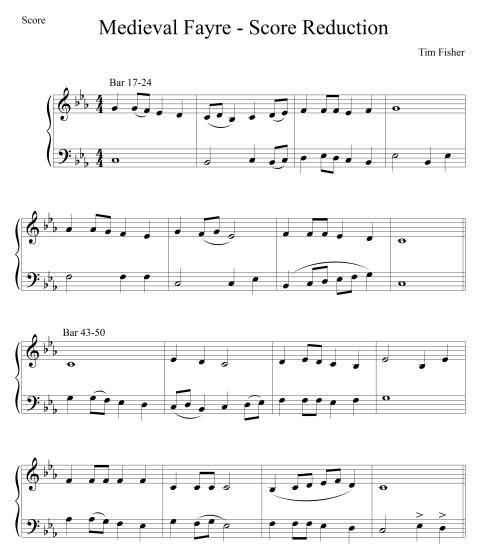

Continuing the idea of writing in other modes apart from straight Bb major (e.g. C Dorian, D Phrygian etc) and of taking a more contrapuntal approach to writing, I wrote Medieval Fayre. This piece is in C Dorian, and like The Forge of Vulcan it has 9 different percussion instruments. Two further concepts influenced this piece, which are outlined below:

At university, I took a music history class with the stunning title – 18th Century Classicism in Music (with a title like that, it’s a wonder it hasn’t been made into a summer blockbuster movie). I don’t remember a great deal from this class (possibly because I may have slept through the odd lecture), but I do remember learning that in Mozart’s Symphony No.41, the final movement is in 5 part invertible counterpoint. (Even if you don’t know what that is, you have to admit that it sounds impressive.) Beginner students can’t play 5 part invertible counterpoint, which is handy because I can’t write 5 part invertible counterpoint. BUT, 2 part counterpoint is ok for them and me. So, in Medieval Fayre, I set out to write a melody and bass line that could be inverted (melody becomes the bass and vice-versa). Here’s what I came up with:

It’s not identical when inverted, but it’s pretty close. It also means that the lower brass and woodwinds get to play the melody and as a consequence they are required to achieve the same level of dexterity as the other players in the band.

It’s not identical when inverted, but it’s pretty close. It also means that the lower brass and woodwinds get to play the melody and as a consequence they are required to achieve the same level of dexterity as the other players in the band.

The final influence stemmed from a question I often ask myself – “What can beginner students be asked do?” We often get caught up with what notes and rhythms the students can and can’t play and forget about all the other elements that make a performance musical. In the case of this piece, I focussed on crescendos. At multiple points through the piece, players are asked to crescendo through a half note (minim) or, in the case of the percussion, crescendo over 4 quavers. This creates musical interest and depth at a level that is achievable for young players.

The concepts and approaches outlined here also apply to other pieces of mine such as Market in Marrakesh (D Phrygian) and Race to the Moon (Bb Lydian Dominant = Bb C D E F G Ab).

The concepts and approaches outlined here also apply to other pieces of mine such as Market in Marrakesh (D Phrygian) and Race to the Moon (Bb Lydian Dominant = Bb C D E F G Ab).

You may find that after reading about some of my pieces, you just have to rush out and get them. I understand this urge completely and in order to help you fulfil your dream, here are some places you can go to buy them: jwpepper.com, sheetmusicplus, or your local band music retailer. If you like them a lot, why not buy copies for your friends and family? If you don’t like them, you can also use the parts for scrap paper, to wrap glassware when moving house, to start a camp fire and a million other things! Order by credit card right now and….

Regal March Analysis #2 (aka What I learned from John O’Reilly)

Well, here is the long-awaited sequel to the smash hit blog post of the summer…Regal March Analysis #1. By all accounts, it’s a non-stop, thrilling roller-coaster ride of emotions. As promised in that post, here is a score reduction of Regal March (RegalMarch_ScoreReduction).

I noted in the previous post that there are only the following “real” parts – Flute, Clarinet, Alto Sax, Trumpet and a generic bass part. The only problem is, at this point I was used to writing for ensembles where I had 3 trumpets, or 2 altos, 2 tenors and a baritone sax. In those cases, voicing a chord was easy – 3 trumpets = root, 3rd, 5th. Simple! The bass part is easy to sort out, but what do you do with the other instruments? How do you voice a chord so that it is balanced? From my analysis of John O’Reilly’s piece I found:

- There are no 3 part triadic structures in the upper voices. It’s always either one or two notes against the bass note (or unison with the bass note). This leaves you with 4 instruments and either 1 or two notes to distribute.

- One note is easy: Cl/AS/Tpt in unison with the Fl 8va (i.e. Fl – CL/AS/Tpt).

- When there are 2 notes to distribute, the most common choice was: Fl – Tpt in octaves = melody note, Cl+AS in unison = harmony note. This is what I primarily used throughout Regal March. It is illustrated here –

- Bearing in mind that the flute will always double one of the other 3 instruments the octave above, your other two choices are:

- Fl – Cl = melody, Tpt+AS = harmony. Given students lack of dynamic control, it’s very easy for the Tpt/AS combination to overpower the Fl – Cl combination

- Fl – AS = melody, Tpt+Cl = harmony.

Some other useful scoring options are:

- High vs Low. I used this approach at b.13-16

- Band vs. Percussion. I used this approach at b.29-33

- WW’s vs Brass. I didn’t use this approach in this piece, but did use it in another easy level piece The Forge of Vulcan. I’ll Look at this piece more closely in later posts.

I also followed John O’Reilly’s pattern in terms of when to change scoring/voicing approach. Notice that in every section, the scoring approach stays relatively constant. For instance in b.5-12 Fl-Tpt = melody, Cl+AS = harmony. At b.13 the approach changes to “high vs low”, then to unison tutti, then returns to the approach used in b.5-12. This does two things – it helps delineate the form, which is good no matter what level you are writing at, and students are able to comprehend what their “job” is quite easily. (e.g. “flutes at b.5-12 you have the melody.”).

That’s all for this week, feel free to add your comments or ask questions.

Regal March Analysis (aka What I learned from John O’Reilly) #1

Well, it’s been crazy concert season at my schools the last few weeks, so I’ve not posted as often as I would have liked (i.e. not at all). But things are calmer this week, so I thought I’d start my anaylsis of my piece Regal March. From my last post you’ll know that before writing this piece, I analysed a few John O’Reilly pieces of a similar standard to better understand how to write at this level. I then shamelessly stole concepts from Mr O’Reilly for my own piece.

By way of background, you need to understand that Regal March (you can find a recording here, and a pdf score here) is a grade 0.5 level piece. It’s aimed at students who have been learning for less than 6 months. It requires only skills learnt in the first 12 or so pages of any beginner method. These are:

- A range of 7 notes – from a concert “A” to the “G” a 7th above (so concert A, Bb, C, D, Eb, F, G)

- Rhythms of a whole note, 1/2 note, 1/4 note and 1/8 notes in pairs, preferably on the same pitch

The first thing to realise is that there are very few “real” parts in this piece. When I first started arranging, I thought something like “Wow, look at all those different instruments, I’ll have to write lots of different parts”. WRONG! Most music consists of 2 layers – foreground (aka the melody) and a background (aka the accompaniment). Sometimes there is only one layer (e.g. a solo melody or a tutti unison – think of the opening of Beethoven Syphony No.5) or sometimes three layers with the addition of a counter-melody. Regal March is a mix of single layer, tutti unison figures and what I think of as 1.5 layers. It’s less of a melody + accompaniment and more of a two part counterpoint or duet. I’ll post a piano reduction of the score soon which makes this much easier to see. So, what can we learn today….

1. There is only 1 clarinet part, 1 trumpet part etc.

At this level, that’s what you whould score for. Only split instruments if absolutely necessary and only for a brief time. This makes the piece much easier for the players – “As long as I sound the same as sarah beside me, I’m on the right note!”, and easier to rehearse – “Trumpets, you should all be playing an “E”. Let’s play an “E” and see if we all sound the same…no remember, 1st & 2nd valves for “E””.

2. There is only one register in which students can play.

The opening few bars are a tutti, unison figure. As the players only have a range of 7 notes, there is only one register on their instrument in which they can play these bars. The end result is 3 octave span scored as follows:

- Flute/Oboe

- Clarinet/Alto Sax/Tenor Sax/Trumpet/Horn

- Bassoon/Bass Clarinet/Baritone Sax/Trombone/Euphonium

- Tuba

At this level, for a tutti, there are really no other choices. The only exception is probably the French Horn. It could have been written an octave lower (with the trombone isntead of the trumpet).

3. There is only one bass part and it is scored the same the entire way through the piece.

There is no “accompaniment” as such in this piece. Rather there is a single note bass line written in counterpoint to the melody And, it is scored the same the whole way through the piece. Bassoon/Bass Clarinet/Baritone Sax/Trombone/Euphonium in unsion with the Tuba an octave below. Sometimes the tuba is given an alternative part an octave higher in unison with the Trombones. This was done to cater for students playing a Eb Tuba rather than a Bb Tuba (this is common in Australia, but rare in the USA).

4. Flute/Oboe are always in unison, so are Alto Sax/Tenor Sax/Horn.

It is very common at this level to write the Flute and Oboe in unsison. Similarly the Alto Sax and French Horn are in unison. This is mainly because Oboes and French Horns are something of a luxury in a beginner band so shouldn’t be given a part entirely by themselves. It’s also difficult for beginners to pitch accurately on a horn when starting out so it helps if they can “follow” another instrument. The Tenor Sax can either double the Alto Sax or double the bass part. In this piece, it the alto part works better for the tenor than the bass part does.

In summary, there are few “real parts”. In fact, the piece can be thought of as only having the following “real parts” – Flute, Clarinet, Alto Sax, Trumpet and a generic bass part.

I’ll go through the rest of the piece and talk about scoring choices in my next post.

If you liked this post and found it helpful, tell your friends, if not, tell your enemies. 🙂