What I Was Trying To Say Was…

In my last post I talked about “having something to say” when writing for beginner bands (or any band for that matter). In this post I’m going to illustrate what I mean by outlining “what I was trying to say” in a couple of my pieces. (Being Valentine’s Day, I did try to say it with flowers. If they didn’t arrive, please contact your local florist.)

The Forge of Vulcan (pub: Brolga Music)

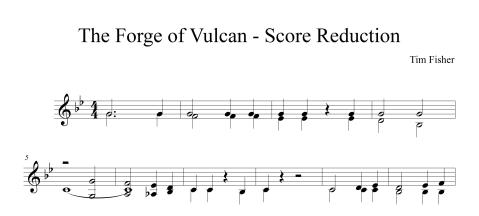

In this piece, I was trying to introduce dissonance in ways that beginner students could cope with and would be able to play successfully. At the time, I had been working through the classic text on counterpoint by Fux – Gradus Ad Parnassum. I realised that if you follow the “rules” about introducing dissonance (prepare it correctly, resolve it correctly), students would/should be able to cope. Hence, I can have the band playing a major 2nd apart for a whole bar (…and loving it!). Notice that the band starts in unison, then moves to the major 2nd, and then resolves to a major 3rd. The dissonance is both prepared and resolved correctly.

Notice that the band starts in unison, then moves to the major 2nd, and then resolves to a major 3rd. The dissonance is both prepared and resolved correctly.

To further improve the clarity of these lines, and to make it easier for students to play, it is scored in a “brass vs woodwinds” kind of way. Initially, the woodwinds all stay static on the “G”, while the brass play the descending line in unison. At bar 5, the roles switch, with the brass remaining static on a “C” whilst the woodwinds play a contrary motion line that starts an octave apart and ends in unison with the brass.

This concept of generating dissonance through oblique motion (i.e. one part moves while the other remains static) extends throughout the piece – e.g. the initial melodic statement in b.9, the B section (b.25-40) and a dominant pedal point later in the piece (b.41-45).

So, I felt comfortable that I had written something with some harmonic interest and gave the low brass as much to do as the other instruments, but what about percussion? The Forge of Vulcan is scored for the following percussion: Glock, Timpani, Snare Drum, Bass Drum, Crash Cymbal, Tambourine, Triangle and Anvil. That should be enough for even the largest percussion section! You could, however, get away with just one player doing Snare Drum and Tambourine with just a little bit of cut ‘n paste.

Tonally, this piece is in C Dorian. It therefore uses the pitch set (Bb major) that the students know at this point, but organises it slightly differently. Personally, I have found it very difficult to write in a straight major key at this level in a way that doesn’t feel like it has already been done.

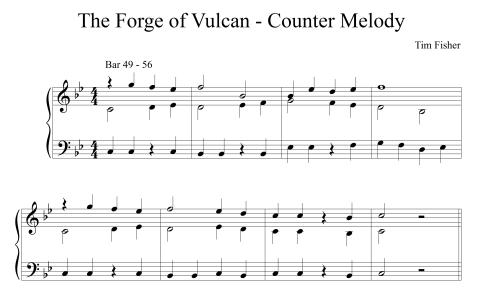

Texturally, the use of a contrapuntal, rather than homophonic (chordal) approach, also helps to make it sound fresher – at least to my ears! For the majority of the piece, there are only 2 lines. But over the final melodic statement, a 3rd line (a countermelody) is introduced into the upper winds and glock parts. At this point in the piece, the rest of the band are playing familiar material and can cope with the addition of another melodic line.

Notice that at times students are playing some quite dissonant harmonies e.g. a minor 7th (F-Eb), a 3 note cluster (G+D+F and C+D+F). It works becuase the lines students play are well constructed and simple within themselves and there is clarity in the way it is orchestrated.

Notice that at times students are playing some quite dissonant harmonies e.g. a minor 7th (F-Eb), a 3 note cluster (G+D+F and C+D+F). It works becuase the lines students play are well constructed and simple within themselves and there is clarity in the way it is orchestrated.

Medieval Fayre (pub: Brolga Music)

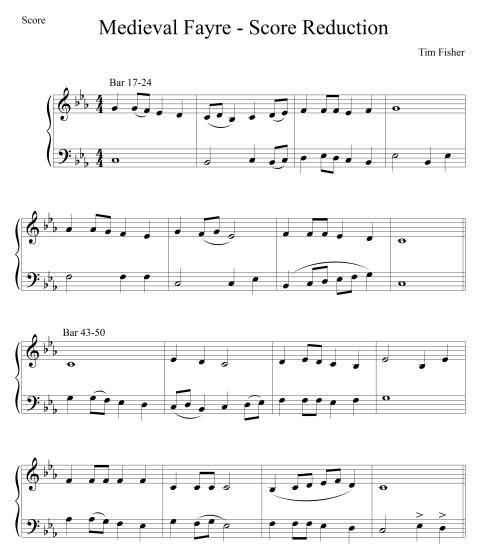

Continuing the idea of writing in other modes apart from straight Bb major (e.g. C Dorian, D Phrygian etc) and of taking a more contrapuntal approach to writing, I wrote Medieval Fayre. This piece is in C Dorian, and like The Forge of Vulcan it has 9 different percussion instruments. Two further concepts influenced this piece, which are outlined below:

At university, I took a music history class with the stunning title – 18th Century Classicism in Music (with a title like that, it’s a wonder it hasn’t been made into a summer blockbuster movie). I don’t remember a great deal from this class (possibly because I may have slept through the odd lecture), but I do remember learning that in Mozart’s Symphony No.41, the final movement is in 5 part invertible counterpoint. (Even if you don’t know what that is, you have to admit that it sounds impressive.) Beginner students can’t play 5 part invertible counterpoint, which is handy because I can’t write 5 part invertible counterpoint. BUT, 2 part counterpoint is ok for them and me. So, in Medieval Fayre, I set out to write a melody and bass line that could be inverted (melody becomes the bass and vice-versa). Here’s what I came up with:

It’s not identical when inverted, but it’s pretty close. It also means that the lower brass and woodwinds get to play the melody and as a consequence they are required to achieve the same level of dexterity as the other players in the band.

It’s not identical when inverted, but it’s pretty close. It also means that the lower brass and woodwinds get to play the melody and as a consequence they are required to achieve the same level of dexterity as the other players in the band.

The final influence stemmed from a question I often ask myself – “What can beginner students be asked do?” We often get caught up with what notes and rhythms the students can and can’t play and forget about all the other elements that make a performance musical. In the case of this piece, I focussed on crescendos. At multiple points through the piece, players are asked to crescendo through a half note (minim) or, in the case of the percussion, crescendo over 4 quavers. This creates musical interest and depth at a level that is achievable for young players.

The concepts and approaches outlined here also apply to other pieces of mine such as Market in Marrakesh (D Phrygian) and Race to the Moon (Bb Lydian Dominant = Bb C D E F G Ab).

The concepts and approaches outlined here also apply to other pieces of mine such as Market in Marrakesh (D Phrygian) and Race to the Moon (Bb Lydian Dominant = Bb C D E F G Ab).

You may find that after reading about some of my pieces, you just have to rush out and get them. I understand this urge completely and in order to help you fulfil your dream, here are some places you can go to buy them: jwpepper.com, sheetmusicplus, or your local band music retailer. If you like them a lot, why not buy copies for your friends and family? If you don’t like them, you can also use the parts for scrap paper, to wrap glassware when moving house, to start a camp fire and a million other things! Order by credit card right now and….

Have Something to Say, Say It With Respect!

Whenever people talk about an artist “having something to say”, my mind immediately goes to a stereotypical angst ridden artist pontificating at great length in a boring voice about how their latest work is a juxtaposition of a basket weaving and a post modern interpretation of the life of cats…this is not what I mean. In fact, I’m not 100% sure what I mean by that phrase (no, please hang in there, it gets better I promise!), but “have something to say” is about the best way I can think of to express the concept I’m trying to get at. A related concept is one that Aretha Franklin said quite well – R.E.S.P.E.C.T. – respect for yourself as a composer and respect for the students who will play your piece. Great, but what does that mean? Here are some thoughts:

- Write something you are proud to put your name to

- Have a reason for writing the piece. I find it useful to be able to complete the sentence I wrote this piece because…

- Write something that has some depth. Even if it’s a supposedly “fluffy” genre like pop. After all, there is some pop music that says something and some pop music that says nothing (compare perhaps Superstition and What Does the Fox Say?).

A story might help illustrate…

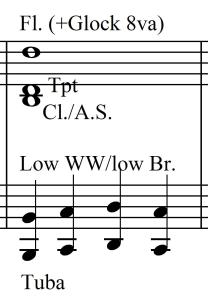

I am a brass player/teacher which means that if I’m assisting at a concert band rehearsal, I often spend most of my time up the back of the room helping out the trumpets, low brass and percussion. Early on in my teaching career I found a couple of things extremely frustrating and I vowed to never write a piece that did either of these things – write percussion parts for only snare drum/bass drum, and to write boring low brass parts. Both of these things, in my opinion, led to a lack of skill development and/or students not wanting to play in band anymore. How on earth can you get trombone players to get excited about music and to improve as players if you write music like this –

I might be exaggerating the flute line a little, but I’ve seen way too many pieces where the low brass play literally that for the WHOLE PIECE! It is just not fair to write that for players. As a band director you also shouldn’t be surprised to you find that your low brass players quit and/or seem incapable of remembering any slide positions or valve combinations if that is what you ask them to play.

I might be exaggerating the flute line a little, but I’ve seen way too many pieces where the low brass play literally that for the WHOLE PIECE! It is just not fair to write that for players. As a band director you also shouldn’t be surprised to you find that your low brass players quit and/or seem incapable of remembering any slide positions or valve combinations if that is what you ask them to play.

Beginner bands tend to have quite a few percussionists. What are you supposed to do when the piece only has a snare drum and a bass drum part and you have 7 percussionists? Triple the parts? I’ve found myself in situations like this where you are trying to get multiple percussionists involved and excited when there are very few parts for them to play – and it’s very difficult. There is a vast array of percussion colors out there – we as composers should use them. It is much easier (in my teaching experience) to have lots of parts but only a few percussionists, or to have lots of percussion instruments required, but you only have a limited number of instruments in your band. As a director, I then just encourage students to find ways to use the gear we have to get as close as possible to the sound the composer was after.

If you are sensing that poor writing for low brass and percussion is something that drives me crackers, you would be right. While I’m listing things that I find frustrating as a band director (and that I try to avoid as a composer) here are two more:

- Boring harmony. Just because you are writing for beginner students does not mean that you can only write straight primary triads in a major key. Personally, I find it very hard to write a piece that sounds fresh and original with just straight (major) primary triads fully voiced. One composer that I love that I think manages to write lots of major triads in an interesting way is Aaron Copland – check out Appalachian Spring

- Boring Form/Mindless Repetition. Repetition is good – compositionally it is one of the ways to tie a piece together and for beginner bands, it gives them less material to learn. But blanket copy and paste is generally boring and (dare I say it) a bit lazy. Re-voice, re-harmonise, re-orchestrate material when it is repeated and you will create a much more interesting work. I played a great piece with my band yesterday that illustrates this idea quite well – The Forbidden City by Michael Story. The same melody is presented 4 different ways, which creates a simple yet interesting piece.

Next time, I will post about a bunch of pieces I’ve written and what I was trying to say. It’s bound to be the most anticipated blog post of the year!

Remember – if you liked this post and found it helpful, tell your friends, if not, tell your enemies. 😉

Odyssey – The Coda

Although I haven’t actually signed a contract yet, I expect that Odyssey will be published later this year. Woo-hoo! I thought it might be useful to let you know the process post sending it off to the publisher. So,

- I send the piece to the publisher for their consideration. I emailed a pdf version of the score, a mp3 generated by Finale and a brief description of the piece. Because I have a relationship with this publisher, I didn’t include any material introducing me.

- The publisher wrote back with a couple of minor suggestions (“have you thought about maybe doubling the Glock part on chimes”) and was enthusiastic about the piece.

- I looked at the suggestions and by and large incorporated them. I then sent back a revised score and a much higher quality mp3 recording generated using East-West Symphonic Orchestra samples (I’ll list details of how I did this at the end)

- The publisher took the score and recording to an editorial board meeting where they review potential repertoire for their new catalogue. The board liked the piece, but also came back with some further minor suggestions

- I looked carefully at their suggestions, incorporated some but not others. I then sent back a revised score and an email detailed what I had changed. Also, quite importantly, I detailed which suggestions I didn’t incorporate and why.

- The publisher replied with one last tweak, and we were done.

From here, I still need to sign a contract. The publisher will organise all the recording, publishing, marketing side of things. The first time I would see a royalty cheque would be late January 2015. So the process from writing a piece to seeing some money is roughly about 18 months.

If you want to know more detail about how I used the EW samples, keep reading, otherwise see you next time!

Using the East West Sample Libraries

First, it’s worth saying that if you are sending a piece to a publisher for consideration, try to send the best recording you can. This may just mean making sure you get the best out of your notation program (can you add some reverb?, can you tweak note lengths, dynamics etc to make it play back better?). In my case, it means using some of the sample libraries I own. Here’s what I do:

- Create a midi file from Finale of my piece. Technically, I could use my samples within Finale (I think), but it’s really, really awkward.

- Import the midi file into my DAW (digital audio workstation – i.e. Cubase, Logic, Digital Performer, Protools, Reaper etc). I use Cubase at the moment. DAW’s are generally a much better tool for manipulating midi data and mixing tracks than trying to use your notation program. I generally try to use the right “tool” for the job. Notate in a notation program, produce audio in a DAW.

- Do a bunch of preliminary editing to tidy up the tracks – glue fragments together, delete midi data my sample don’t recognise, copy and paste midi data (where required) to the correct midi controller for my samples, break up the tracks into various sample patch types. This means putting all the staccato notes on one track, all the legato notes on another track etc.

- Load up the samples from the East West libraries and press play! In my case I’m working on an old laptop that chokes if I try to run an entire band of samples. So I do sections at a time (e.g. all the clarinet parts), check that they work, render to audio so I can unload those samples and load a new set.

- Mix the tracks

- Add some reverb (if necessary)

- Create an mp3 (High Quality mp3 though)

Hopefully that makes sense – let me know if you have questions.

You can read about the rest of the process of writing this piece here, here and here.

It Is Finished…Pas Deux

Yep, I’ve finished my new piece Odyssey for the second time, and this time it’s personal! [You can read about how I started this piece here, and a progress post here]. How do you finish a piece twice you ask? To answer that, it helps to explain my writing process. (Bear in mind that this is how I tend to work, but everyone is different). My writing process goes like this:

- The initial idea. Where these initial ideas come from, I don’t know. Sometimes they just pop into my head out of the blue, sometimes they come from playing piano and I just hit something or play something that I like or find interesting. Sometimes they come from a kind of musical brainstorming session (i.e. write 3 melodies of 8 bars in 5 minutes), and other times its just from deciding to write a modal blues in G Dorian.

- Development. This is where I take that initial idea and develop it into something longer – maybe an “A” section and an intro

- I get stuck. Surprisingly, this is the part of the process where I get stuck. I’ve run out of inspirational steam, but I’ve only got about 1/3 to 1/2 of the piece written and I don’t know quite where to go from here. You don’t have to be Einstein to guess that this isn’t the fun part of writing. To get unstuck, I try:

- Drinking coffee

- Cleaning my study

- Checking email

- Putting my head in the sand

- After these don’t really help, I try:

- Thinking about the piece structurally – what is the form of this piece going to be?

- What would contrast with what I already have (loud vs soft, fast vs slow, solo vs tutti etc)

- Just write something and not worry too much about whether it’s “good” or not. After all you can edit it later, or chuck it completely if you want

- In fairness to points 3.1 – 3.4, taking a break does help sometimes

- The piece is finished! – for the first time. It’s not really finished, but it feels like it. At this point I’ve got the main pieces in place, right through to the end. It might be sketchy in places, but at least in my head I know what I’m trying to do all the way through. [Here is Odyssey at this point – Odessey – In Progress (concert pitch)]

- Refinement. At this point I edit, cut, smooth, shape, polish, wrestle, hammer, the piece into shape. Sketchy ideas are fleshed out. Often this is particularly true of percussion parts which have often ranged from sketchy to “vague notion in my head” to non-existent. [Here is Odyssey at this point –Odyssey – In Progress #2 (concert pitch)] For me, this stage is iterative – evaluate –> refine –> evaluate —> refine repeatedly until….

- The piece is finished! – for the second time. This time, it really is finished…almost. [Here is Odyssey at this point –Odyssey – In Progress #3]

- Idiot Check. This is where I print out the score (it really is easier to read on paper than on a screen) and check for any silly little errors – missing dynamics/articulations, stuff I forgot to fill in etc.

- Perform/Send to a publisher. I’ll be sending this to a publisher I already have a relationship with. Assuming they want to publish it, it will likely come back with a few editorial suggestions/comments. 90% of the time, you should do what they suggest.

It’s worth re-stating at this point that you should edit your work and don’t be afraid to delete things that don’t work. I went and had lunch after my last post, came back and deleted an 8 bar section that didn’t work. It has also taken a fair bit of “hammering” to get the last 30 bars to work. If you compare versions #2 and #3, you’ll see that the framework has stayed essentially the same, but the detail has changed.

Thanks for reading, I’m off to check for idiots…

A Piece Is Born – Update

It’s finished! Well, not really, but kind of…confused yet?

Since last I posted, here’s what I’ve done. I managed to spend a few hours shortly after finishing my last blog post (here it is) working on my new piece for Concert Band. In that time I did the following:

- Thought of a name – Odyssey

- Wrote a chorale theme to go with the opening fanfare theme

- Decided form-wise to go straight into the chorale following the introduction. It was tempting to go into a rhythmic, march type vibe and just restate the opening melody, but I decided to avoid that approach as I’ve used it before and just felt a little too obvious in this case.

- Setup a score in Finale

- Sketch in the introduction and opening chorale theme

- Decided to score the chorale for just flute and clarinets (+oboe maybe?) the first time through

- For the second time through the chorale, I’m going to give the melody to the a.sax + cl. + f.hn. My intention is to have the remaining brass and lower woodwinds play reasonably static chords to support the melody. The upper voice of this accompaniment may effectively turn out to be a quasi counter-melody.

It has then sat idle for a couple of weeks due to life being crazy and working somewhere else on my “writing day” until today. This morning I’ve spent another couple of hours working on it and you can look at my in progress score here Odessey – In Progress (concert pitch). Here’s what I’ve done this morning:

- Tweaked the tempo slightly from 116 to 108bpm. It just felt a little rushed at 116bpm

- Added the brass to the second time through the chorale. This might not be exactly how it finishes up, but it’s in the ballpark

- Form-wise, it felt to me like the opening fanfare melody should come back twice and that would roughly be the end of the piece. This meant:

- Deciding how to transition from the chorale back into the fanfare theme. I’ve used a classic device whereby the last part of the chorale is restated in longer (augmented would be the fancy music word here) note vales. I’ve also changed the harmony slightly so that the return to a “C” pedal feels like a key change.

- This in turn led to the quasi introduction type section at bar 31-38 with the clarinets playing a simplified version of the fanfare melody, with a “sparkly” response from the fl/ob+tpts.

- At this point, keeping the low brass and woodwinds on the same rhythmic figure for yet another two times through the fanfare melody seems like a long time for beginners to cope with. It’s also a bit boring for the listener. So I’m going to try to “get out” of that rhythmic figure at bar 39. I’m not sure whether I’ll keep the percussion going through here, and/or whether to have the accompaniment be sustained notes or stop time type “hits”

- Getting out of the continuous rhythmic accompaniment at bar 39, also creates more interest at bar 50 when it returns for the final statement of the fanfare theme.

- The piece finishes with the same compositional technique that I used earlier in the piece, namely, restating the end of the theme and then augmenting note values to create a sense of the piece slowing down before the big finish.

At this point, the piece is finished…kind of. I feel at this point that all the main structural elements are in place and that I’ve got a good idea of how it will be scored. If this piece were a table, I feel that I had all the main pieces cutout and stuck together. Now what remains is to sand, polish, and add “pretty bits”. Sp my to do list for this piece is now:

- Resolve the accompaniment at bar 39

- Finish scoring all the woodwind and brass parts. Notice that there is nothing in the bassoon, bass clarinet or baritone saxophone parts yet. These will end up doubling bass lines already present in the trombone/euphonium/tuba parts

- Score the percussion. Again, there is nothing on paper, but I have a good idea in my head of what these will look like. The percussion in this piece will largely augment the woodwind and brass parts, rather than supply an independent voice. This isn’t always the case and if there was a specific independent percussion part I wanted, it would be in the score by now. The percussion will likely end up with:

- Timpani – doubling the pedal bass line. Timpani is great for this as the player doesn’t get tired in the same way that a wind player does when playing for an extended period without a break

- Snare drum, Bass drum, Cymbals – these will play march/fanfare figures. Think John Williams Olympic fanfare type stuff.

- Glock/Vibes – the glock will end up doubling some melodic lines. I’m not really expecting to use the vibes, but it’s easier to have the line there in the score when setting it up just in case. If it’s not used, I’ll just delete it.

- Edit, tweak, refine until I’m happy. E.g. I’m still debating about making bar 37 a 2/4 bar (and losing two beats at this point).

Once that’s all done, I’ll more than likely leave it for a week or so, and come back and look at it again and make sure I’m happy. If not, then more refining, tweaking, editing until I am.

I’m off to have lunch…

A Piece Is Born

When students see my name at the top of a piece of music, we often have a conversation that goes a little like this:

Student: “Sir, did you write this piece?”

Me: “Yes”

Student: (somewhat in disbelief) “Really?”

Me: “Yes”

Student: (clearly traumatized by this seismic worldview shift) “So you like, wrote this whole piece…”

Me: “Yes”

Student: (in a desperate effort to restore balance to the force) “Did you copy it out from a book?”

Me: “No, I wrote it”

Student: (flailing helplessly in a whirlpool of despair) “like, all of it, or just like, umm, like, the trumpet part?”

This can sometimes continue for quite a while as students wrestle with the concept of a composer who isn’t dead. After the student has exhausted themselves trying to grapple with reality, they ask two other questions:

- Student: “Do you make lots of money?” Me: “I make so much money writing music, I can afford to keep teaching you.” (student looks puzzled)

- Student: “How did you write it?” or “How long did it take to write?”

To answer the last two questions, I thought I’d post about a piece as I write it.

So far this (as yet untitled) piece has taken 3 months, and all I’ve got is 5 bars! (Wow, that’s slow progress Tim!) Here’s what’s happened so far.

Three months ago I was taking a composition class at a music camp. The first activity I get students to do is to write a 4 or 8 bar melody in C major using only basic note values. I usually set a fast deadline (i.e. 10mins) to encourage them to just write something and not try to turn it into their great masterwork. The plan is then to see what they come up with and start from there for the rest of the class. As the students were writing their melody, I thought I’d write a few melodies of my own. Here’s what I came up with.

In order to write a bunch of melodies quickly, I made a choice about tempo, feel, and time signature before starting (C major was a given). Then I wrote the first thing that occurred to me, with my only pitch reference being my own voice. This is a bit like musical brain storming and it can be a useful way to generate some ideas. Most might be rubbish, but something might just be the seed for something really good. These melodies made such an impact on me that I forgot about them for 3 months! The piece of manuscript ended up in my laptop bag, forgotten – until yesterday when I packed up my laptop to go away. I glanced at the piece of paper enough to be able to sing the first two bars of one of the third melody. Since then I’ve been singing those two bars around in my head and thinking about how to expand them into a piece.

When starting a piece you should think about the level you are targeting. It’s very difficult once you’ve written a piece to make it easier, or harder. Once that is decided, you should think about other main structural/starting point questions around choice of key, tempo, form and length.

Here’s what I’ve been thinking about so far:

- Level: I’d like to try and keep this piece at about Gr 0.5

- Tempo: I’ve been singing it at approximately 116bpm. This works as a march/fanfare type tempo.

- Key: Initally it was in C major because that was the starting point for my class, but this doesn’t mean it’s the best choice. So, how to choose a good key? Trumpets make an obvious choice to play the opening two bars. So what key suits the trumpets best? The obvious choices are concert Bb major or maybe concert Eb major. I’m leaning towards Eb major as the higher key makes the trumpets a little brighter and I haven’t written much in Eb.That second one isn’t the world’s greatest reason, except that often choosing a different key or tempo or time signature can help you write something different to what you’ve written before.

- I am conscious of not going too high or else it will take the trumpets out of a reasonable register for this level piece. I’d like to try and keep the highest note for the trumpets to be a written Bb, with maybe one or two written C’s at the climax. Written D is a no-no.

- I would like to “tweak” the melody or harmony in some way to try and avoid a straight up, inside, Eb major vibe.

- In bed this morning I came up with this:

- It’s an Apollo 13 soundtrack (or this) kind of vibe. I like the fact that it’s a 5 bar phrase (3+2) and that’s it’s not a straight major tonality. But, I would rather avoid having the trombones playing such a prominent note in 5th position (Db). So back to thinking about key. Is there a better choice?

- Eb major – has trombones playing Db in a significant way, early on in the piece. Not a great percentage move.

- Bb major – it’s getting a bit low. What’s in-between? You can eliminate B, Db and D major straightaway. No-one plays that many sharps and flats at this level. This only leaves:

- C major – this isn’t a great key signature at this easy level. But,wait a minute, my opening phrase is really a mixolydian phrase! This means I can use a key signature of C mixolydian (=1 flat, aka F major) – way less scary for students at this level.This also makes the low brass and woodwinds enter on a concert C, and then a concert Bb. High percentage moves at any level!

So, some take away points from what I’ve done so far are: ·

- Always write down your ideas – good, bad or ugly. You never know when you might rediscover them. ·

- If you are stuck, just write something! BUT, make some choices before you start – it will be in G minor, 3/4, a ballad, and I’m going to start on the 5th degree of the scale. Then start writing. See what you can come up with in 10mins.

- Edit yourself! You must edit yourself! Assume you are not as talented as Mozart and that your first idea won’t be absolutely perfect.

- Know the capabilities of students at the grade level you are writing for. Try and choose keys and registers that will give your piece the best chance of success.

So get writing and we’ll meet back here in year or so with the next 8 bars 🙂

Regal March Analysis #2 (aka What I learned from John O’Reilly)

Well, here is the long-awaited sequel to the smash hit blog post of the summer…Regal March Analysis #1. By all accounts, it’s a non-stop, thrilling roller-coaster ride of emotions. As promised in that post, here is a score reduction of Regal March (RegalMarch_ScoreReduction).

I noted in the previous post that there are only the following “real” parts – Flute, Clarinet, Alto Sax, Trumpet and a generic bass part. The only problem is, at this point I was used to writing for ensembles where I had 3 trumpets, or 2 altos, 2 tenors and a baritone sax. In those cases, voicing a chord was easy – 3 trumpets = root, 3rd, 5th. Simple! The bass part is easy to sort out, but what do you do with the other instruments? How do you voice a chord so that it is balanced? From my analysis of John O’Reilly’s piece I found:

- There are no 3 part triadic structures in the upper voices. It’s always either one or two notes against the bass note (or unison with the bass note). This leaves you with 4 instruments and either 1 or two notes to distribute.

- One note is easy: Cl/AS/Tpt in unison with the Fl 8va (i.e. Fl – CL/AS/Tpt).

- When there are 2 notes to distribute, the most common choice was: Fl – Tpt in octaves = melody note, Cl+AS in unison = harmony note. This is what I primarily used throughout Regal March. It is illustrated here –

- Bearing in mind that the flute will always double one of the other 3 instruments the octave above, your other two choices are:

- Fl – Cl = melody, Tpt+AS = harmony. Given students lack of dynamic control, it’s very easy for the Tpt/AS combination to overpower the Fl – Cl combination

- Fl – AS = melody, Tpt+Cl = harmony.

Some other useful scoring options are:

- High vs Low. I used this approach at b.13-16

- Band vs. Percussion. I used this approach at b.29-33

- WW’s vs Brass. I didn’t use this approach in this piece, but did use it in another easy level piece The Forge of Vulcan. I’ll Look at this piece more closely in later posts.

I also followed John O’Reilly’s pattern in terms of when to change scoring/voicing approach. Notice that in every section, the scoring approach stays relatively constant. For instance in b.5-12 Fl-Tpt = melody, Cl+AS = harmony. At b.13 the approach changes to “high vs low”, then to unison tutti, then returns to the approach used in b.5-12. This does two things – it helps delineate the form, which is good no matter what level you are writing at, and students are able to comprehend what their “job” is quite easily. (e.g. “flutes at b.5-12 you have the melody.”).

That’s all for this week, feel free to add your comments or ask questions.

Regal March Analysis (aka What I learned from John O’Reilly) #1

Well, it’s been crazy concert season at my schools the last few weeks, so I’ve not posted as often as I would have liked (i.e. not at all). But things are calmer this week, so I thought I’d start my anaylsis of my piece Regal March. From my last post you’ll know that before writing this piece, I analysed a few John O’Reilly pieces of a similar standard to better understand how to write at this level. I then shamelessly stole concepts from Mr O’Reilly for my own piece.

By way of background, you need to understand that Regal March (you can find a recording here, and a pdf score here) is a grade 0.5 level piece. It’s aimed at students who have been learning for less than 6 months. It requires only skills learnt in the first 12 or so pages of any beginner method. These are:

- A range of 7 notes – from a concert “A” to the “G” a 7th above (so concert A, Bb, C, D, Eb, F, G)

- Rhythms of a whole note, 1/2 note, 1/4 note and 1/8 notes in pairs, preferably on the same pitch

The first thing to realise is that there are very few “real” parts in this piece. When I first started arranging, I thought something like “Wow, look at all those different instruments, I’ll have to write lots of different parts”. WRONG! Most music consists of 2 layers – foreground (aka the melody) and a background (aka the accompaniment). Sometimes there is only one layer (e.g. a solo melody or a tutti unison – think of the opening of Beethoven Syphony No.5) or sometimes three layers with the addition of a counter-melody. Regal March is a mix of single layer, tutti unison figures and what I think of as 1.5 layers. It’s less of a melody + accompaniment and more of a two part counterpoint or duet. I’ll post a piano reduction of the score soon which makes this much easier to see. So, what can we learn today….

1. There is only 1 clarinet part, 1 trumpet part etc.

At this level, that’s what you whould score for. Only split instruments if absolutely necessary and only for a brief time. This makes the piece much easier for the players – “As long as I sound the same as sarah beside me, I’m on the right note!”, and easier to rehearse – “Trumpets, you should all be playing an “E”. Let’s play an “E” and see if we all sound the same…no remember, 1st & 2nd valves for “E””.

2. There is only one register in which students can play.

The opening few bars are a tutti, unison figure. As the players only have a range of 7 notes, there is only one register on their instrument in which they can play these bars. The end result is 3 octave span scored as follows:

- Flute/Oboe

- Clarinet/Alto Sax/Tenor Sax/Trumpet/Horn

- Bassoon/Bass Clarinet/Baritone Sax/Trombone/Euphonium

- Tuba

At this level, for a tutti, there are really no other choices. The only exception is probably the French Horn. It could have been written an octave lower (with the trombone isntead of the trumpet).

3. There is only one bass part and it is scored the same the entire way through the piece.

There is no “accompaniment” as such in this piece. Rather there is a single note bass line written in counterpoint to the melody And, it is scored the same the whole way through the piece. Bassoon/Bass Clarinet/Baritone Sax/Trombone/Euphonium in unsion with the Tuba an octave below. Sometimes the tuba is given an alternative part an octave higher in unison with the Trombones. This was done to cater for students playing a Eb Tuba rather than a Bb Tuba (this is common in Australia, but rare in the USA).

4. Flute/Oboe are always in unison, so are Alto Sax/Tenor Sax/Horn.

It is very common at this level to write the Flute and Oboe in unsison. Similarly the Alto Sax and French Horn are in unison. This is mainly because Oboes and French Horns are something of a luxury in a beginner band so shouldn’t be given a part entirely by themselves. It’s also difficult for beginners to pitch accurately on a horn when starting out so it helps if they can “follow” another instrument. The Tenor Sax can either double the Alto Sax or double the bass part. In this piece, it the alto part works better for the tenor than the bass part does.

In summary, there are few “real parts”. In fact, the piece can be thought of as only having the following “real parts” – Flute, Clarinet, Alto Sax, Trumpet and a generic bass part.

I’ll go through the rest of the piece and talk about scoring choices in my next post.

If you liked this post and found it helpful, tell your friends, if not, tell your enemies. 🙂

In the beginning…

This blog is me (Tim Fisher) thinking aloud about writing for Concert Band – primarily junior level bands. I’ll be talkiing about how I got started writing for concert band, how I approach writing for band and things I’ve learned about writing for band. I’ll be thinking and learning as this blog goes along, both through the process of writing it and from feedback from readers like you. This means that it’s entirely possible that I will change my mind about issues as time goes on – nothing is set in stone!

So, how did I get started?

I had completed an undergraduate degree in music where we had to write arrangements for our class. This is always tricky because you never have a balanced ensemble, it’s usually some weird mix of 4 singers, viola, 2 flutes, one trumpet and bagpipes…how do you write for that! But in the process I found great orchestration books like: Rimsky Korsakov’s Princples of Orchestration, Walter Piston’s Orchestration, and Samuel Adler’s The Study of Orchestration. These are great places to start if you don’t already know what the range of a flute is or how a trumpet transposes or how a trombone works.

I had also been writing for jazz ensemble, so I had found books like: The Complete Arranger by Sammy Nestico, Inside the Score by Rayburn Wright and Arranging for Large Jazz Ensemble by Dick Lowell & Ken Pullig.

But as great as these books are, they still leave you a bit short of information when it comes to writing for Concert Band. There are no strings (the heart of the orchestra), and no rhythm section (the backbone of a big band). And, at junior level band writing, you only have one trombone part, not 3, one trumpet part, not 3 or 4, one alto sax, one tenor sax and so on. What to do? The secret is to do what orchestrators and arrangers have been doing for centuries – study the work of other writers to find out what they did. In my case that meant getting some scores of easy works for concert band (grade 0.5 and 1.0) by John O’Reilly and reducing them to a concert pitch, short score. I then tried to figure out some standard chord and melodic line voicings, doublings and other techniques that he used. Armed with this information, I then wrote my first piece for Concert Band – Regal March. It’s not destined to become a master work for band, but it’s a solid piece of writing for a concert band at the Gr 0.5 level.

So what should you do?

- Find a couple of pieces that are similar to what you want to write, then get the score and study it. If you don’t have access to scores, you can by them pretty easily from places like jwpepper.com

- Write and arrange something yourself using what you’ve learnt from your score study

- Keep reading my blog! In the next post I’ll talk about the writing techniques I used in Regal March

see you next time….