A Piece Is Born

When students see my name at the top of a piece of music, we often have a conversation that goes a little like this:

Student: “Sir, did you write this piece?”

Me: “Yes”

Student: (somewhat in disbelief) “Really?”

Me: “Yes”

Student: (clearly traumatized by this seismic worldview shift) “So you like, wrote this whole piece…”

Me: “Yes”

Student: (in a desperate effort to restore balance to the force) “Did you copy it out from a book?”

Me: “No, I wrote it”

Student: (flailing helplessly in a whirlpool of despair) “like, all of it, or just like, umm, like, the trumpet part?”

This can sometimes continue for quite a while as students wrestle with the concept of a composer who isn’t dead. After the student has exhausted themselves trying to grapple with reality, they ask two other questions:

- Student: “Do you make lots of money?” Me: “I make so much money writing music, I can afford to keep teaching you.” (student looks puzzled)

- Student: “How did you write it?” or “How long did it take to write?”

To answer the last two questions, I thought I’d post about a piece as I write it.

So far this (as yet untitled) piece has taken 3 months, and all I’ve got is 5 bars! (Wow, that’s slow progress Tim!) Here’s what’s happened so far.

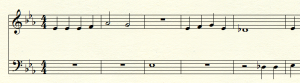

Three months ago I was taking a composition class at a music camp. The first activity I get students to do is to write a 4 or 8 bar melody in C major using only basic note values. I usually set a fast deadline (i.e. 10mins) to encourage them to just write something and not try to turn it into their great masterwork. The plan is then to see what they come up with and start from there for the rest of the class. As the students were writing their melody, I thought I’d write a few melodies of my own. Here’s what I came up with.

In order to write a bunch of melodies quickly, I made a choice about tempo, feel, and time signature before starting (C major was a given). Then I wrote the first thing that occurred to me, with my only pitch reference being my own voice. This is a bit like musical brain storming and it can be a useful way to generate some ideas. Most might be rubbish, but something might just be the seed for something really good. These melodies made such an impact on me that I forgot about them for 3 months! The piece of manuscript ended up in my laptop bag, forgotten – until yesterday when I packed up my laptop to go away. I glanced at the piece of paper enough to be able to sing the first two bars of one of the third melody. Since then I’ve been singing those two bars around in my head and thinking about how to expand them into a piece.

When starting a piece you should think about the level you are targeting. It’s very difficult once you’ve written a piece to make it easier, or harder. Once that is decided, you should think about other main structural/starting point questions around choice of key, tempo, form and length.

Here’s what I’ve been thinking about so far:

- Level: I’d like to try and keep this piece at about Gr 0.5

- Tempo: I’ve been singing it at approximately 116bpm. This works as a march/fanfare type tempo.

- Key: Initally it was in C major because that was the starting point for my class, but this doesn’t mean it’s the best choice. So, how to choose a good key? Trumpets make an obvious choice to play the opening two bars. So what key suits the trumpets best? The obvious choices are concert Bb major or maybe concert Eb major. I’m leaning towards Eb major as the higher key makes the trumpets a little brighter and I haven’t written much in Eb.That second one isn’t the world’s greatest reason, except that often choosing a different key or tempo or time signature can help you write something different to what you’ve written before.

- I am conscious of not going too high or else it will take the trumpets out of a reasonable register for this level piece. I’d like to try and keep the highest note for the trumpets to be a written Bb, with maybe one or two written C’s at the climax. Written D is a no-no.

- I would like to “tweak” the melody or harmony in some way to try and avoid a straight up, inside, Eb major vibe.

- In bed this morning I came up with this:

- It’s an Apollo 13 soundtrack (or this) kind of vibe. I like the fact that it’s a 5 bar phrase (3+2) and that’s it’s not a straight major tonality. But, I would rather avoid having the trombones playing such a prominent note in 5th position (Db). So back to thinking about key. Is there a better choice?

- Eb major – has trombones playing Db in a significant way, early on in the piece. Not a great percentage move.

- Bb major – it’s getting a bit low. What’s in-between? You can eliminate B, Db and D major straightaway. No-one plays that many sharps and flats at this level. This only leaves:

- C major – this isn’t a great key signature at this easy level. But,wait a minute, my opening phrase is really a mixolydian phrase! This means I can use a key signature of C mixolydian (=1 flat, aka F major) – way less scary for students at this level.This also makes the low brass and woodwinds enter on a concert C, and then a concert Bb. High percentage moves at any level!

So, some take away points from what I’ve done so far are: ·

- Always write down your ideas – good, bad or ugly. You never know when you might rediscover them. ·

- If you are stuck, just write something! BUT, make some choices before you start – it will be in G minor, 3/4, a ballad, and I’m going to start on the 5th degree of the scale. Then start writing. See what you can come up with in 10mins.

- Edit yourself! You must edit yourself! Assume you are not as talented as Mozart and that your first idea won’t be absolutely perfect.

- Know the capabilities of students at the grade level you are writing for. Try and choose keys and registers that will give your piece the best chance of success.

So get writing and we’ll meet back here in year or so with the next 8 bars 🙂

Regal March Analysis (aka What I learned from John O’Reilly) #1

Well, it’s been crazy concert season at my schools the last few weeks, so I’ve not posted as often as I would have liked (i.e. not at all). But things are calmer this week, so I thought I’d start my anaylsis of my piece Regal March. From my last post you’ll know that before writing this piece, I analysed a few John O’Reilly pieces of a similar standard to better understand how to write at this level. I then shamelessly stole concepts from Mr O’Reilly for my own piece.

By way of background, you need to understand that Regal March (you can find a recording here, and a pdf score here) is a grade 0.5 level piece. It’s aimed at students who have been learning for less than 6 months. It requires only skills learnt in the first 12 or so pages of any beginner method. These are:

- A range of 7 notes – from a concert “A” to the “G” a 7th above (so concert A, Bb, C, D, Eb, F, G)

- Rhythms of a whole note, 1/2 note, 1/4 note and 1/8 notes in pairs, preferably on the same pitch

The first thing to realise is that there are very few “real” parts in this piece. When I first started arranging, I thought something like “Wow, look at all those different instruments, I’ll have to write lots of different parts”. WRONG! Most music consists of 2 layers – foreground (aka the melody) and a background (aka the accompaniment). Sometimes there is only one layer (e.g. a solo melody or a tutti unison – think of the opening of Beethoven Syphony No.5) or sometimes three layers with the addition of a counter-melody. Regal March is a mix of single layer, tutti unison figures and what I think of as 1.5 layers. It’s less of a melody + accompaniment and more of a two part counterpoint or duet. I’ll post a piano reduction of the score soon which makes this much easier to see. So, what can we learn today….

1. There is only 1 clarinet part, 1 trumpet part etc.

At this level, that’s what you whould score for. Only split instruments if absolutely necessary and only for a brief time. This makes the piece much easier for the players – “As long as I sound the same as sarah beside me, I’m on the right note!”, and easier to rehearse – “Trumpets, you should all be playing an “E”. Let’s play an “E” and see if we all sound the same…no remember, 1st & 2nd valves for “E””.

2. There is only one register in which students can play.

The opening few bars are a tutti, unison figure. As the players only have a range of 7 notes, there is only one register on their instrument in which they can play these bars. The end result is 3 octave span scored as follows:

- Flute/Oboe

- Clarinet/Alto Sax/Tenor Sax/Trumpet/Horn

- Bassoon/Bass Clarinet/Baritone Sax/Trombone/Euphonium

- Tuba

At this level, for a tutti, there are really no other choices. The only exception is probably the French Horn. It could have been written an octave lower (with the trombone isntead of the trumpet).

3. There is only one bass part and it is scored the same the entire way through the piece.

There is no “accompaniment” as such in this piece. Rather there is a single note bass line written in counterpoint to the melody And, it is scored the same the whole way through the piece. Bassoon/Bass Clarinet/Baritone Sax/Trombone/Euphonium in unsion with the Tuba an octave below. Sometimes the tuba is given an alternative part an octave higher in unison with the Trombones. This was done to cater for students playing a Eb Tuba rather than a Bb Tuba (this is common in Australia, but rare in the USA).

4. Flute/Oboe are always in unison, so are Alto Sax/Tenor Sax/Horn.

It is very common at this level to write the Flute and Oboe in unsison. Similarly the Alto Sax and French Horn are in unison. This is mainly because Oboes and French Horns are something of a luxury in a beginner band so shouldn’t be given a part entirely by themselves. It’s also difficult for beginners to pitch accurately on a horn when starting out so it helps if they can “follow” another instrument. The Tenor Sax can either double the Alto Sax or double the bass part. In this piece, it the alto part works better for the tenor than the bass part does.

In summary, there are few “real parts”. In fact, the piece can be thought of as only having the following “real parts” – Flute, Clarinet, Alto Sax, Trumpet and a generic bass part.

I’ll go through the rest of the piece and talk about scoring choices in my next post.

If you liked this post and found it helpful, tell your friends, if not, tell your enemies. 🙂

In the beginning…

This blog is me (Tim Fisher) thinking aloud about writing for Concert Band – primarily junior level bands. I’ll be talkiing about how I got started writing for concert band, how I approach writing for band and things I’ve learned about writing for band. I’ll be thinking and learning as this blog goes along, both through the process of writing it and from feedback from readers like you. This means that it’s entirely possible that I will change my mind about issues as time goes on – nothing is set in stone!

So, how did I get started?

I had completed an undergraduate degree in music where we had to write arrangements for our class. This is always tricky because you never have a balanced ensemble, it’s usually some weird mix of 4 singers, viola, 2 flutes, one trumpet and bagpipes…how do you write for that! But in the process I found great orchestration books like: Rimsky Korsakov’s Princples of Orchestration, Walter Piston’s Orchestration, and Samuel Adler’s The Study of Orchestration. These are great places to start if you don’t already know what the range of a flute is or how a trumpet transposes or how a trombone works.

I had also been writing for jazz ensemble, so I had found books like: The Complete Arranger by Sammy Nestico, Inside the Score by Rayburn Wright and Arranging for Large Jazz Ensemble by Dick Lowell & Ken Pullig.

But as great as these books are, they still leave you a bit short of information when it comes to writing for Concert Band. There are no strings (the heart of the orchestra), and no rhythm section (the backbone of a big band). And, at junior level band writing, you only have one trombone part, not 3, one trumpet part, not 3 or 4, one alto sax, one tenor sax and so on. What to do? The secret is to do what orchestrators and arrangers have been doing for centuries – study the work of other writers to find out what they did. In my case that meant getting some scores of easy works for concert band (grade 0.5 and 1.0) by John O’Reilly and reducing them to a concert pitch, short score. I then tried to figure out some standard chord and melodic line voicings, doublings and other techniques that he used. Armed with this information, I then wrote my first piece for Concert Band – Regal March. It’s not destined to become a master work for band, but it’s a solid piece of writing for a concert band at the Gr 0.5 level.

So what should you do?

- Find a couple of pieces that are similar to what you want to write, then get the score and study it. If you don’t have access to scores, you can by them pretty easily from places like jwpepper.com

- Write and arrange something yourself using what you’ve learnt from your score study

- Keep reading my blog! In the next post I’ll talk about the writing techniques I used in Regal March

see you next time….